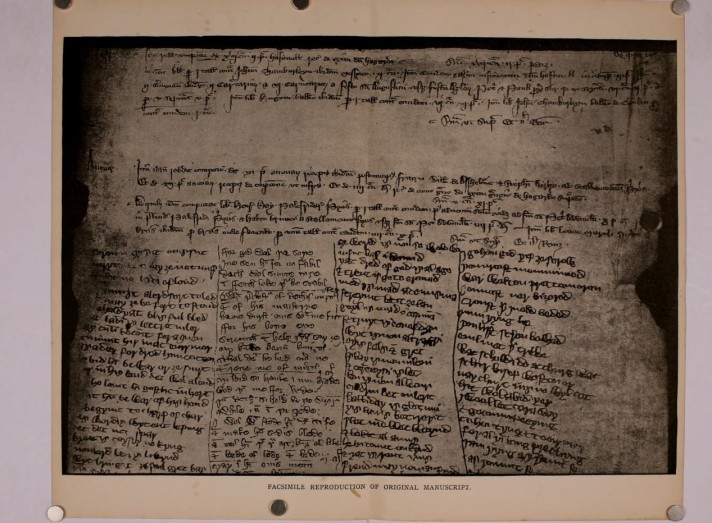

There are many images that might be considered fundamental, or at least quite useful, to a robust undergraduate course on early drama: the stage plan from The Castle of Perseverance, the woodcuts from Skot’s edition of Everyman, Denijs van Alsloot’s painting of the Brussels ommegang pageant wagons, Cailleau’s resplendent painting of the Valenciennes Passion set. For me, however, one of the most significant and revealing images from the period is that messy, faded, photozincographic facsimile of the play-fragment The Pride of Life.

- Photozincographic facsimile of the manuscript containing the-14th-century play The Pride of Life

(Part of Roll 235, formerly in the Christ Church Collection, PRO, Dublin), Royal Society of Antiquities of Ireland.

The Victorian antiquarian James Mills had the facsimile made for his 1891 edition of The Account Roll of the Priory of the Holy Trinity, Dublin, 1337-1346,[1] in which he printed the text of the fragmentary play with the image as the frontispiece. For me, the facsimile-image is a vivid testament to the haphazard survival of so many medieval texts, as well as a telling reminder of drama’s inherent ephemerality.

Arguably the earliest surviving English ‘morality play’, The Pride of Life presents the allegorical story of Rex Vivus (‘King of Life’) and his foolish attempt to challenge Death to a fight-to-the-death, which of course he cannot win. The King of Life’s presumption is supported by his courtly flatterers, his knights Strength and Health, and he is ultimately unmoved by the pleas of his wife and the sermonizing of the local Bishop: he refuses to reform and show humility. The King eventually meets his fate on the battlefield, struck down by Death, yet the play’s banns let us know that ‘Oure Lady mylde’ (l. 97) will intercede on his behalf. Deus ex machina-like, she will secure the release of the King’s soul, ‘That the fendis have ikaghte’ (l. 106).

It is a curious survival: fragmentary and so unlike many later English ‘morality’ plays. Yet it shares tropes and themes with other medieval and early modern dramatic texts: warning us about the dangers of pride, the insidiousness of flattery, the certainty of death, and the undeserved availability of salvation, even at the point of death.

-

- King Herod and his knights, roof boss, Norwich Cathedral, c. 1470

And the facsimile-image itself tells a story of salvation at the point of destruction: the fragment of the play which survived was scribbled, haphazardly, in the blank spaces of a 14th-century account roll of Dublin’s Priory of the Holy Trinity (‘Christ Church’), apparently by members of the Priory’s Augustinian community. It was written in two different hands – the first ‘clerky’ and the second ‘irregular’ (Mills) – literally crammed into four wobbly columns beneath a run of accounts (and this disorganised quality is obvious in the facsimile-image). Presumably two ‘brothers’ of the community (their exact identity is unknown) found the play important enough to copy it down – somewhere, anywhere – and it seems they simply used the blank space on the nearest available parchment roll.

The play is indeed Anglo-Irish. The spelling forms of the two scribes differ greatly (Mills was of the opinion that one of them probably did not speak English as a first language), and it could be that one was working from dictation. Some early editors (such as Mills) were misled by place names such as Mirth’s referencing ‘here to Berwick-on-Tweed’ (l. 285), believing them to signal English provenance. However, this seems to be a mere folk-expression, meaning ‘[from] here to wherever’ or similar, and is not indicative of an original from England.[2] The play seems to have been composed in Ireland for the Anglo-Irish audience, and some of its peculiar spelling forms and the details of its manuscript survival support this notion. However, it prefigures that popular fifteenth- and sixteenth-century taste for moral, allegorical drama that will prove immensely popular across the British Isles.

Mills’s facsimile-image of the manuscript raises some intriguing questions: is it a record of performance or a copy-of-a-copy (or both)? What was it about this play, among the countless others undoubtedly performed in and around Dublin over the centuries, that merited its survival (why this odd little play)?

But the Pride of Life fragment’s unique survival story doesn’t end there: during the Irish Civil War which followed partition in 1921, The Dublin Four Courts building was occupied by troops opposed to the new Dublin government. Shelled by the National Army, the building was eventually gutted by fire, resulting in the destruction of Ireland’s Public Records Office and its collection of valuable manuscripts – including the Priory account roll. All that survives of the roll and of the play is Mills’ 1891 edition with its and single photozincographic image.

The unique journey of the earliest English morality play – from initial, transitory performance; to the minds and memories of medieval scribes; to the crowded margins of a Priory account roll; to a Victorian antiquarian’s specialist edition – is a particularly fascinating example of the circuitous routes early play texts often take to reach us. Yet that grainy image from The Pride of Life reminds us that drama’s true spirit is in performance, not on the page: the play is an event, existing in space and time, with an audience, destined for ephemerality. However, on rare occasion, fortune intercedes, allowing the soul of the play a chance to live again.

Possible points for discussion:

The Pride of Life is fragmentary, with the biggest missing section the play’s conclusion. However, the opening banns to the play tell us a bit about what should happen next. First read the play, then answer the following questions:

- How would you conclude The Pride of Life if you were going to direct it today?

- What are some of the theological implications to be considered when reconstructing those missing parts of the play?

- What are the drawbacks of recreating parts of an incomplete play text such as this? And are there advantages?

The play’s survival is a testament to the often fortunate, circuitous, or piecemeal ways in which pre-modern play texts reach us. Consider history of the Pride of Life’s text alongside the facsimile image that survives, then answer the following questions:

- What, if anything, can the play’s textual history teach us about how some medieval plays were composed and transmitted?

- Why do you think the play’s copyists wrote it down? What might have been their motivation?

- As so few play texts survive, where else might we look for evidence of popular drama and entertainment in the medieval period?

- What can the play’s textual history tell us about the nature of manuscript culture in the period? (a look at the history of the Winchester Manuscript of Malory’s Morte D’Arthur might make an interesting comparison).

[1] Non-Cycle Plays and Fragments, ed. Norman Davis, EETS, SS 1 (London: OUP, 1970), p. xcvi.

[2] Reproduction with new intro. by J. Lydon and A. J. Fletcher (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1996). The play and facsimile are also printed in Non-Cycle Plays and Fragments.

Mark Chambers

University of Durham

Excellent post, Mark! Will steal for my medieval drama class.

Offering here video links to the PLS UK productions from 2016, in which we allowed the audience to decide how to fill the holes in the play (with apologies, the actors sometimes also improvised their explanation about the details of the MS’s survival!):